I've been trying to think of a word that sums up 2017. The first few that spring to mind are uncertainty, change, exhaustion, and adaptation. A few on a slightly more positive note would be wonder, gratitude, and love. In short, there is no one word to encompass the monumental life achievements and transitions of the past year, along with their highs and lows. I am happy to have made it through relatively intact...and looking forward to 2018.

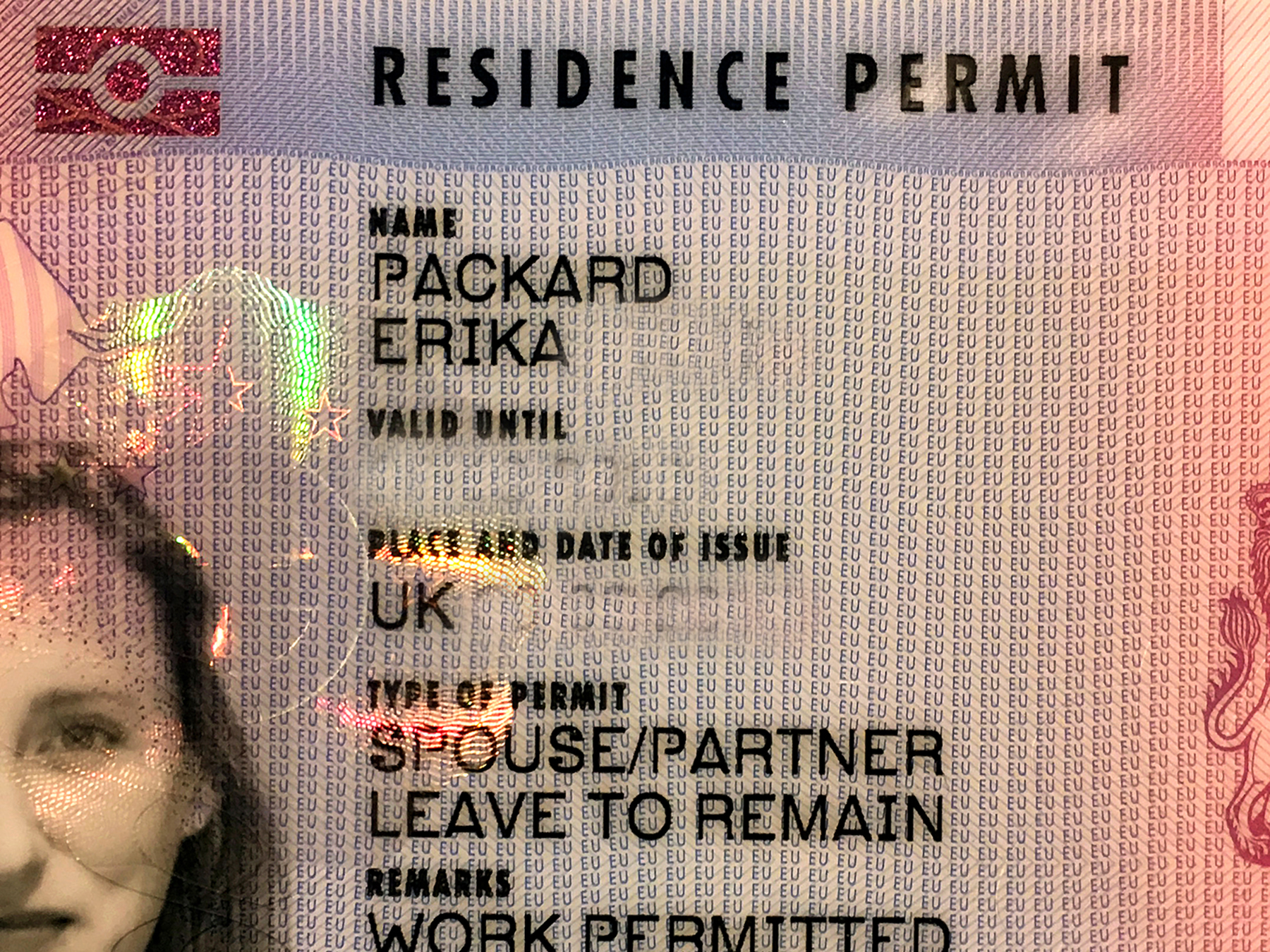

Last year's review post featured lots of exotic foreign travel and and world-class gardens. In 2017 I was too busy to leave the British Isles. I finished my horticulture degree, learned to drive a manual car on the left side of the road and passed my U.K. driving test. I got married, obtained my next U.K. visa, moved to south-east England, bought a car, re-adapted to life in the country, and found and began my first professional horticultural job.

Mixed in with all the life groundwork above were some truly beautiful moments, the finest of which was without a doubt my wedding. There were other highlights including a class outing to the Victorian fernery on the isle of Bute, a trip to Broadwoodside garden in June, a visit from my parents in July, and my first trip to RHS Wisley, which helped assuage the pain of missing Edinburgh's Botanics. A much-needed trip to London this past week topped up my depleted reserves of art, culture, and delicious food. Even simpler pleasures were time spent walking along the Water of Leith in Edinburgh, spotting kingfishers and otters. I walked miles a day in that beautiful city, taking in all I could before I knew I'd have to leave.

Now that I am starting to stabilize into the next phase of my life, I plan on spending 2018 exploring as much of southern England as I can and visiting the many famous gardens planted in this warmer and sunnier part of Britain. I'm looking forward to wearing shorts and sandals for the first time in this country, fingers crossed. I hope to take advantage of living almost within sight of France and generous vacation time to do more trips to the Continent. Along with my husband, I am excited to plan, plant, and tend our first garden--the seeds of which were my favorite Christmas present. Most important, I'd like to gather my strength to plan the next step in my brand-new horticultural career, in which I want to combine my technical gardening skills with my writing and photography to teach people about plants.

Wherever you are, thanks for reading along, and have a wonderful new year.